Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement v. State of Iowa

The Iowa Supreme Court has done it again. By a narrowly divided vote, it has snuffed out on procedural grounds litigation challenging the agricultural nutrient pollution of the Raccoon River.

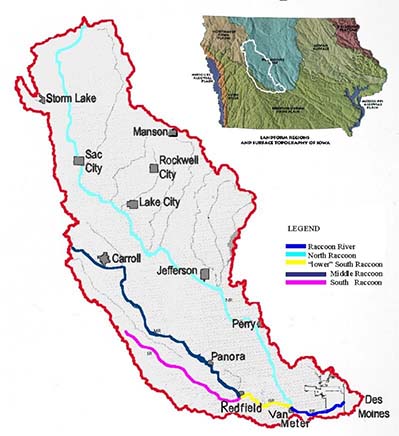

The Raccoon River rises in central Iowa, an area of exceptional agricultural productivity, especially corn, soybeans, and hogs. The agricultural activity contributes large quantities of nutrient pollution to the river. This agricultural nutrient pollution has long been the focus of controversy, particularly because the city of Des Moines uses the Raccoon River as a source of drinking water.

The Iowa Supreme Court’s first brush with the agricultural pollution of the Raccoon River involved a citizen suit in federal court by the Des Moines Water Works against the county supervisors who operate systems of tile drains that draw excess water from agricultural fields and convey it to the headwaters of the Raccoon River upstream of the Des Moines. The Des Moines Water Works alleged the agricultural drains were point sources that required NPDES permits, and the water works sought monetary damages to recoup the costs of treating the river water to remove excess nitrates due to the agricultural pollution. On questions referred to it by the federal district court, the Iowa Supreme Court held that the county supervisors were immune from suit under Iowa law. In light of the Iowa Supreme Court’s answer on the referred questions, the federal district court dismissed Des Moines Water Works’ federal citizen suit. The federal court held that the Des Moines Water Works lacked standing because the court believed it could not grant relief against the county supervisors that would redress the injuries alleged in the complaint. Facing threats from the Iowa legislature to dissolve the water works as a public body, the Des Moines Water Works chose not to appeal. The following year, the legislature capped things off by passing legislation that enshrined Iowa’s voluntary nutrient reduction strategy as the state’s official policy for addressing nutrient pollution.

The Iowa Supreme Court’s more recent brush with agricultural pollution of the Raccoon River arose out of a complaint filed in state court in 2019 by two public interest groups against the state of Iowa and the Iowa agencies and officials responsible for administering the state’s environmental and agricultural programs. The complaint alleged the state defendants had an affirmative duty under the public trust doctrine to protect the Raccoon River against agricultural pollution that impaired use of the river for recreational and drinking water purposes. The complaint sought a variety of declaratory and injunctive relief, including a declaration that the state had breached the public trust; a declaration that the legislation codifying the voluntary nutrient reduction strategy was unconstitutional; an order requiring the state to adopt a remedial plan implementing mandatory agricultural pollution controls, and an injunction prohibiting new or expanded animal feeding operations in the watershed. The state defendants moved to dismiss the suit on grounds that: (i) the plaintiffs lacked standing, (ii) their claim involved a non-justiciable political question, and (iii) the plaintiffs had failed to exhaust administrative remedies. The trial court denied the motion to dismiss, and the state filed a request for interlocutory appeal.

The Iowa Supreme Court granted interlocutory review; and by a vote of 4-3 it reversed the trial court and remanded with instructions to dismiss the suit. The majority acknowledged that in Iowa the public trust doctrine applies to the state’s navigable waters, but the majority held that the doctrine is narrow and only protects public ownership of, and access to, the state’s navigable waterbodies. The majority concluded the plaintiffs lacked standing because they could not obtain relief that would redress their injuries, given the narrow nature of the public trust doctrine in Iowa. The majority also concluded that the plaintiffs’ suit should be dismissed because their claims for relief presented non-justiciable political questions.

Three justices dissented, arguing that the majority opinion improperly adopted federal standing requirements of causation and redressability that had never been a part of Iowa state law. The dissents also argued that the majority improperly used the standing issue as a justification to rule on the merits of the plaintiffs’ public trust claim. According to the dissents, the state defendants had accepted for purposes of their motion to dismiss the proposition that the plaintiffs had stated a valid claim under Iowa’s public trust doctrine.

The Iowa Supreme Court’s latest decision on the Raccoon River is another illustration of the dysfunctional state of U.S. environmental law when it comes to agricultural water pollution. Everybody knows that water pollution from agricultural sources is a major problem throughout the country. Everybody knows there are straightforward management practices and technologies that could significantly reduce agricultural water pollution. Voluntary programs have failed to solve the problem, and market-based trading solutions have rarely gotten serious traction. For fifty years the Clean Water Act has exempted agriculture from federal regulation and left the problem for the states to regulate. And for fifty years the states have mainly looked the other way. Citizen suits and other more imaginative litigation have made little headway in forcing a solution. Until there is a strong federal program driving improvement, it is difficult to see how the problem of agricultural water pollution will be solved. Perhaps the next Farm Bill could be the legislative vehicle, and eligibility to participate in farm programs could be the jurisdictional hook.

Republished with permission. Originally published on the American College of Environmental Lawyers (ACOEL) blog.

The Between the Lines blog is made available by Mitchell, Williams, Selig, Gates & Woodyard, P.L.L.C. and the law firm publisher. The blog site is for educational purposes only, as well as to give general information and a general understanding of the law. This blog is not intended to provide specific legal advice. Use of this blog site does not create an attorney client relationship between you and Mitchell Williams or the blog site publisher. The Between the Lines blog site should not be used as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed professional attorney in your state.